Fostering innovation by unlearning tacit knowledge

The Authors

Miroslav Rebernik, Faculty of Economics and Business, Institute for

Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, University of Maribor, Maribor,

Slovenia

Karin Širec, Faculty of Economics and Business, Institute for Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management, University of Maribor, Maribor, Slovenia

Abstract

Purpose – The aim of this paper is to investigate the problems of

managing tacit knowledge and the importance of unlearning it. As the main

problem of managing tacit knowledge lies in the fact that it escapes observation

and measurement, an adequate framework that would make some dimensions of tacit

knowledge visible has to be developed.

Design/methodology/approach – On the basis of literature surveys

the authors discuss several types of knowledge and issues related to sharing,

learning and, most importantly, unlearning obsolete tacit knowledge dimensions.

Findings – To overcome the perpetual elusiveness of tacit

knowledge is presented a framework that could help highlight dimensions of tacit

knowledge that can be mobilized and observed through the manifestation of

different behaviour. It is partly possible to make explicit some dimensions of

tacit knowledge that not only contribute to successful sharing and mutual

learning, but also enable the identification of those parts of knowledge that

hinder innovation and should be unlearned. The better one's understanding of the

process of creating and using new knowledge and discarding obsolete knowledge,

the more likely it is that organizations will foster innovative behaviour in

organizations.

Originality/value – Introduced insight is

important in understanding the importance of the distinctive requirements of

knowledge management related to managing tacit dimensions. In the turbulent and

ever-changing business environment, tacit knowledge dimensions grow obsolete

very rapidly and hinder innovation processes, so ways of un-learning this

obsolete knowledge have to be found.

Article Type:

Research paper

Keyword(s):

Cybernetics; Innovation; Knowledge management.

Journal:

Kybernetes

Volume:

36

Number:

3/4

Year:

2007

pp:

406-419

Copyright ©

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

ISSN:

0368-492X

Introduction

The development of “hypercompetition” (D'Aveni, 1994) and shortened product lifecycles has reduced the degree to which much special knowledge can provide companies with a sustained competitive advantage. On the one hand, companies are increasingly realizing that their knowledge base is the basis of their competitive advantage (Svelby, 1997). On the other hand, they realize that innovation is paramount to sustain these advantages. To be prepared for new business opportunities, a company must permanently innovate and change its resources, so that new resources will be adequate for the exploitation of new business opportunities. Schumpeter (1934) called this evolutionary process creative destruction.

In knowledge society aimed at sustainable development, the exchange of knowledge among different agents is of crucial importance. To embrace incoming knowledge and use it productively, a critical mass of knowledge and skills has to be present already in the organization. Without an appropriate knowledge base, new knowledge cannot be absorbed. In the absorption process, learning – and un-learning – takes place. Learning and un-learning is continually taking place in all knowledge areas and with all types of knowledge, which makes the phenomena very complex and hard to comprehend, especially because the processes are mutually dependent on social, cultural, economic and political contexts, which differ from country to country. The better we understand the process of creating and using knowledge, the more likely organizations will foster innovative behaviour. Some authors (Von Krogh et al., 2000) argue that “the creation of knowledge cannot be managed, but only enabled”.

Developing countries and transitional economies lack experiential knowledge to a greater extent than mature market economies. Understanding organizations as information processing systems, where experiential knowledge is stored in organizational memory (Christensen et al., 2004) brings an important caveat for transitional post-communist countries. During their “previous existence” in socialism/communism these countries accumulated much experiential knowledge that has since grown obsolete and should be disposed of because it has become useless and impedes the accumulation of new knowledge that is so essential for innovation and competitiveness to occur. Data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor reveals that in transitional countries newly formed companies display low innovativeness, because these businesses are based on old technologies and with local customers. At the same time these countries have a very low share of high-growth potential companies and low value added per employee in established firms (Rebernik et al., 2006; Minniti, 2006; Autio, 2005).

This paper seeks to enhance the understanding of the learning and unlearning processes in the area of tacit knowledge. The innovation process demands a focus different from that of other business activities, specifically, to nurture open access to people's extensive tacit knowledge – the one “in and between minds” (Armbrecht et al., 2001, p. 28). A company's culture and structure will be the critical factors enabling knowledge flow (Armbrecht et al., 2001, p. 28). So the next imperative for companies to achieve sustainability of its competitive advantage is to create superior knowledge management capabilities, and thereby foster ongoing innovation.

In this paper, we first present a simple verbal model to show the complexity of different types of knowledge and the learning/unlearning process. Second, we analyse the contribution of tacit knowledge to innovation and the problems encountered in tacit knowledge management. At the end of the paper, we introduce a theoretical concept of how to unlearn tacit knowledge to promote the innovation processes.

Types of knowledge

Knowledge is a living asset; dynamic and volatile, often difficult to observe and understand. Unlike information, it is not final and stored, but emerging and being constantly recreated and socially reconstructed in particular work contexts. Knowledge may be tangible or intangible by its nature. Know-how, when articulated into the organization's database and operating technologies is tangible. Similarly, explicit knowledge is tangible because it has been encoded into documents, databases, or some other permanent medium (Meso and Smith, 2000, p. 232).

All kinds of knowledge together, as an emerging synergy, make knowledge a system which, in combination with values, needs and possibilities, is the starting point of any human action (Mulej et al., 2000). Thus, knowledge is an important part of a more complex system.

On the other hand, the knowledge resources of organizations have pertinently been described as an iceberg. Structured, explicit knowledge is the visible top of the iceberg. This part of the knowledge resource is easy to find and recognize, and therefore also rather easy to share. Beneath the surface of conscious thought lies a vast sea of tacit knowledge, derived from a lifetime of experience, practice, perception and learning. This concept is captured in Polanyi's (1958, 1966) often-quoted statement, “We know a lot more than we can express” and therefore this part of the intangible knowledge resource can be more difficult to share (Haldin-Herrgard, 2000, p. 358).

In many industries, success in today's markets depends on the ability to learn about emerging market opportunities, and to rapidly develop and spread the knowledge necessary to exploit them, rather than on careful long-term planning. The key driver of superior performance today is the ability to change when the environment calls for it, and to find the shifting sources of advantage. As a result of these changes, the ability to acquire, develop and spread new knowledge has become an indispensable core competence.

The ability to create new and valuable breakthroughs offers companies an unambiguous competitive advantage. Therefore, it is very important for a company to enable an environment that will encourage unique, original and unexpected innovations, which are far more valuable from a competitive standpoint than innovations that are predictable, incremental or mundane (Lynn et al., 1996).

Such an imperative requires a shift in the role of management. In a knowledge-based economy managers have to manage the environment or context in which work is done, rather than controlling the workers themselves (Stewart, 1997; Svelby, 1997). The manager will serve as a coach and facilitator, a boundary-buster and head cheerleader. His or her role will be to eliminate the barriers that prevent individuals from performing at their optimum levels. Success in the new economy requires a new form of vision-based leadership (Davenport, 1993, pp. 117-37).

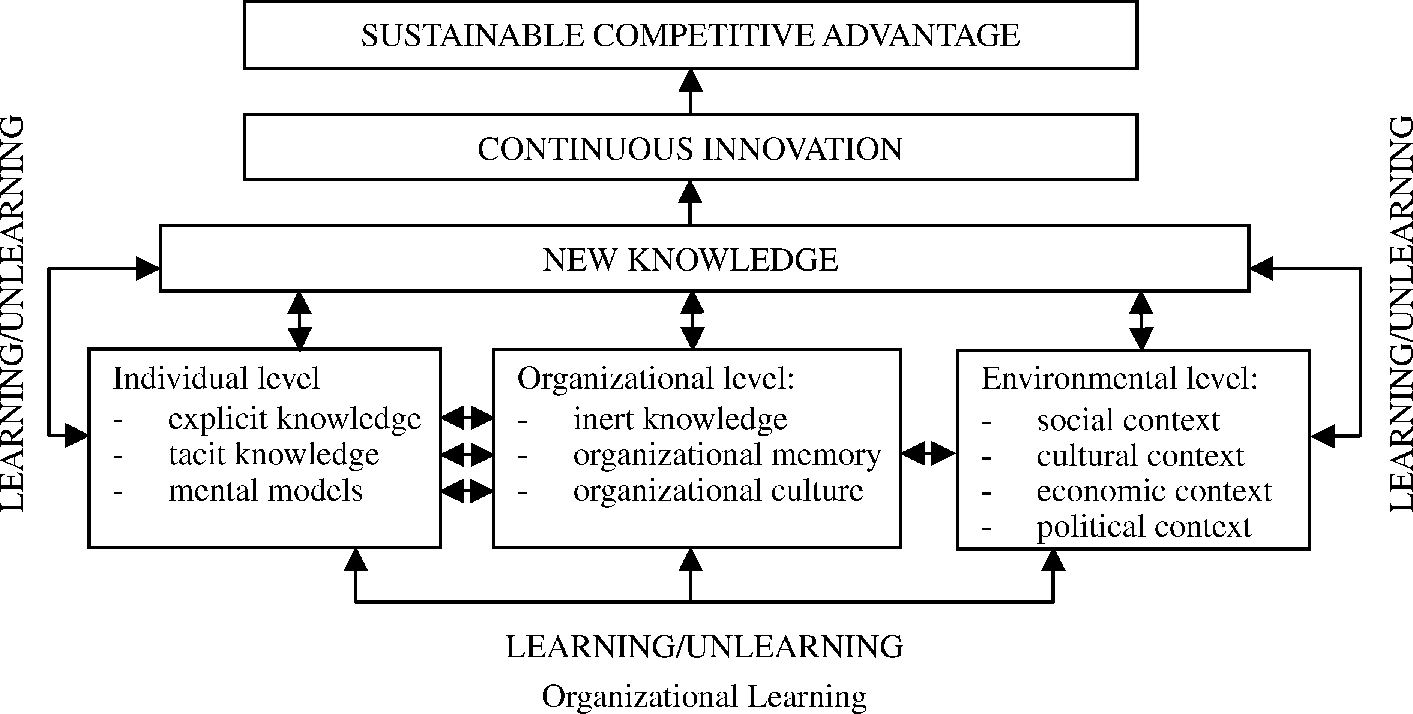

This problem is multidimensional in its nature. It must be managed at individual and organizational level, as well as in the social, cultural, economic and political contexts. All three levels have a number of factors considered to be parallel. We present them in Figure 1.

At the individual level, researchers and writers have identified the difference between explicit and tacit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is widely accepted as knowledge that is recognized by the individual and therefore easily expressed or articulated (Durrance, 1998; Newell et al., 2002; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Roy and Roy, 2002). Explicit knowledge is sometimes referred to as codified knowledge.

At the organizational level, explicit knowledge is generally found captured in a static form. This knowledge, which is easily articulated and documented, can be found in organizational policies, procedures and processes, as well as in documentation such as performance management systems and position descriptions (Becker, 2006).

Tacit (or implicit) knowledge entails information that is difficult to express, formalize and share. It stands in contrast to explicit knowledge, which is conscious and can be put into words. People experience tacit knowledge mostly as intuition, rather than as a body of facts or instruction sets he or she is conscious of having and can explain to others. Tacit knowledge is obtained by internal individual processes, such as experience, reflection, internalisation or individual talent. Therefore, it cannot be given in lectures and found in databases, textbooks, manuals or internal newsletters for diffusion. It has to be internalised in the human body and soul (Haldin-Herrgard, 2000, p. 358).

At the organizational level organizational memory in many ways reflects tacit knowledge, although more has been written about organizational memory in the field of information technology than in the general management literature. Many authors purpose different definitions and explanations for organizational memory (Argyris and Schon, 1978; Stein, 1995; Levit and March, 1988; Paoli and Principe, 2003), and they all recognize that organizational memory is not just explicit knowledge that is captured, but importantly, that it also has a tacit dimension.

The third level considered within the model focuses at individual level on mental models (Kim, 1993), and at organizational level on culture. Beside mental models, many other terms can be found in the literature, such as frames of reference (Mezirow, 2000 in Becker, 2006), cognitive maps (Huber, 1991), schemas (Barrett et al., 1995), theories of action (Hedberg, 1984) and paradigms (Markoczy, 1994 in Becker, 2006). We will follow the definition of Mezirows, who describes them as those deep-seated underlying values and belief systems that guide, shape and dictate the individual's everyday attitudes and behaviours. Culture has long been seen as the shared or commonly held beliefs, assumptions, values and taken-for-granted norms and behaviour that govern organizations (Becker, 2006).

On an environmental level companies face the challenge of exchanging knowledge among different agents. The phenomena become very complex and hard to comprehend, especially because processes are mutually dependent on the social, cultural, economic and political contexts, which are different from country to country, and therefore not easily transferred (Rebernik, 1997; Tominc and Rebernik, 2006).

Learning and unlearning

Many definitions of organizational learning and knowledge sharing exist (Hedberg, 1984; Cummings, 2003; Argyris, 2004; Esterby-Smith and Lyles, 2005). According to the definition that:

… an organization learns in only two ways:

- (a) by the learning of its members, or

- (b) by ingesting new members who have knowledge the organization did not previously have (Simon, 1991, p. 125)

We should also pay attention to the individual level, as learning and unlearning takes place at both levels.

If, according to Johanson and Vahlne (1990) knowledge is stored in the decision-making system, when decision makers leave the company, knowledge is lost. Many new companies in the post Berlin Wall era were formed in transitional countries by “drop-out” managers of large and medium-sized companies. As many managers of previously (big) socialist companies have formed their own companies, usually as sole proprietorships, the experiential knowledge embedded in organizational routines has been lost. Large and medium-sized companies have lost the expertise gained through innovation processes, while newly formed companies (very often, one-man bands) lack the human and financial resources to innovate.

The hierarchy of routines (Nelson and Winter, 1982) would lead us to the conclusion that changing the dominant beliefs of top managers could be the answer. But here again, we enter the twilight zone of transitional economies, where institutional arrangements are not established yet, rules of the game and the structures of payoffs (Baumol, 1990) are not determined, many agency problems exist, false cooperation (Rebernik, 1999) is taking place, and requisite holism is missing (Rebernik and Mulej, 2000). For unlearning to take place, intentional forgetting of some parts of existing individual and organizational knowledge is needed. Firms must “disorganize” some part of their knowledge store (Holan de et al., 2004). Similar disorganization must also take place at individual level. The complexity of never-ending learning and unlearning processes is shown in Figure 1.

Tacit knowledge and innovation

Tacit knowledge often allows us to perform at a higher level than our explicit knowledge does. For example, novices cannot become experts simply by exposure to explicit information; they need to experience the activity itself and co-operation relating to it. For these reasons, the success of a manager is heavily dependent on tacit knowledge. Therefore, supporting the sharing of tacit knowledge throughout the company will be possible with methods like apprenticeship, direct interaction, networking and action learning that includes face-to-face social interaction and practical experiences.

There are four categories of tacit knowledge (Lubit, 2001, p. 166):

- Hard-to-pin-down skills. “Know-how”; the word skill implies tacit knowledge. People need to repeatedly practice skills, receive feedback and get a feel for them.

- Mental models. We draw on mental models or schemas when trying to make sense of a situation; they determine how we understand and analyse situations; that is, how we understand cause-effect connections and what meaning we attribute to events. The schemas we use are often subconscious abstractions, rather than explicit models we consciously employ, and therefore they belong to tacit knowledge. They affect whether or not we see people as trustworthy, whether we see opportunity in a situation, and how we judge risk.

- Ways of approaching problems. Tacit knowledge underlies the decision trees people use.

- Organizational routines. Much of a firm's tacit knowledge is stored in its routines. This tacit knowledge embedded in routines includes an intuitive grasp of what data to focus on and of the relative priority of competing demands. In time, managers leave and the routines remain as a legacy of their knowledge.

The difficulty of expressing, codifying and transmitting tacit knowledge makes it easier for a company to protect it than explicit knowledge. Moreover, tacit knowledge may only be effective when embedded in a particular organizational culture, structure and set of processes and routines. The difficulty of copying tacit knowledge enables tacit knowledge to be the basis of an inimitable competitive advantage.

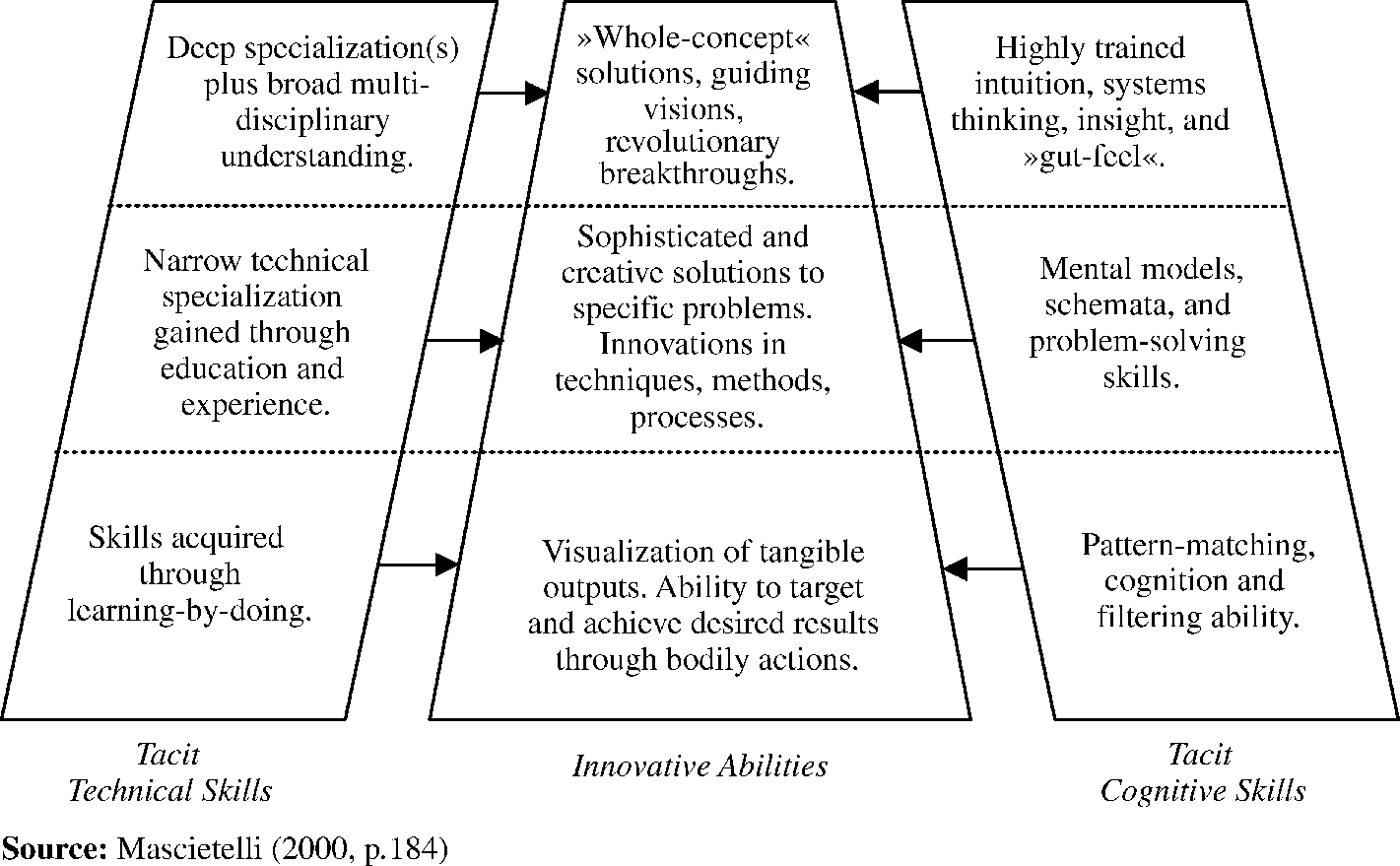

Tacit knowledge can take on several forms, each of which offers unique advantages to innovation, as shown in Figure 2.

At the most fundamental level there is the knowledge gained through “learning-by-doing”. A specialist engineer or technologist represents a second category of innovator; one whose knowledge is gained through a combination of formal education and work experience in his specialty.

As the pace of change continues to accelerate, the importance of tacit knowledge and outstanding knowledge management capabilities have to be recognised as critical to the ongoing success of organisations through successful innovation. In the following paragraph we resume the difficulties in managing tacit knowledge in the way that effective unlearning is going to be proposed as one of the solutions for fostering innovation processes.

Managing tacit knowledge

In the next paragraph we are going to present difficulties related to effective management of tacit knowledge. First, we need to address difficulties in sharing tacit knowledge linked with perception and language. The sub-consciousness of tacit knowledge and the difficulty of expressing it are commonly found as the main problems in tacit knowledge diffusion. It is not only that we have difficulty expressing and articulating what we know; we may not even be conscious of what we know or how tacit knowledge connects to our explicit knowledge.

The consumption of time that the internalisation tacit knowledge requires must also be seen as a difficulty in the sharing process. In today's business world time is a scarce resource, and the internalisation of new experiences or knowledge is a process over time (Halding-Herrgard, 2000, p. 361). This difficulty with time is attributed to personal tacit knowledge as well as to more organizational forms. There seems to be a shift from functional organizing and functional management, to process organizing and process management (Hammer and Champy, 1993). The task of functional management is completed in different departments, while the task of process management is handed out in process teams with a “hands-on” approach to the whole process (Lewis, 1995, in Johannessen et al., 1999, p. 132).

We should also point out difficulties related to values. Knowledge is a basis for power and respect, and people are often hesitant to share knowledge lest their power decreases. Moreover, sharing knowledge requires that time be taken away from other responsibilities that have a higher priority. People are not only hesitant to share what they have, but they also are hesitant to use the knowledge of others. This has been referred to as the “not invented here” syndrome.

The limited efficacy of most knowledge-management efforts has come about because they have focused overwhelmingly on creating electronic means to capture and store information and improve communication. Far more attention needs to be given to the task of convincing people to effectively use the information system (Lubit, 2001, p. 173).

Further, difficulties can be found regarding distance. Social interaction is often seen as a necessity for the diffusion of tacit knowledge. The globalisation, diversification and virtualisation of business that obstruct face-to-face interaction are, therefore, a threat to tacit knowledge diffusion.

Perhaps, the most important step toward harnessing the tacit knowledge of individuals and teams is to allow it to flow from the pull of emotional commitment and deep personal involvement (Glynn, 1996 in Mascitelli, 2000, p. 185). Therefore, the challenge for managers is to inspire, guide, excite, encourage, and shape, without overwhelmingly imposing arbitrary structures that might destroy the fragile essence that separates breakthrough innovation from uninspired incrementalism.

For example, managers can foster the genuine commitment of design team members on three different levels (Mascitelli, 2000, p. 187) by:

- crafting a “culture of innovation” for the company as a whole;

- establishing a strong sense of group identity, importance and purpose among project team members; and

- creating a generative environment for knowledge sharing – where learning, as well as unlearning, occurs.

Another factor encouraging knowledge sharing is procedural justice in decision making. Research (Lubit, 2001, p. 175) has shown that when managers feel strategic decision-making processes are fair they tend to cooperate voluntarily. Procedural justice has three aspects: engagement, explanation and clarity. When these three aspects of procedural justice are fulfilled, company employees are most likely to both share their ideas and carry out decisions which are made.

Effective knowledge management includes dealing with the defensive mechanisms that impede communication. Common defensive mechanisms include avoiding the discussion of important issues, giving ambiguous messages and distorting information. To avoid these phenomena is very important to develop a culture which values openness, tolerates failures, encourages questioning of the way things are conducted and permits workers to challenge their superiors (Lubit, 2001, p. 175).

Tacit-to-tacit exchange is greatly enhanced by close personal contact. That is why physical co-location and face-to-face interaction can be important catalysts for innovation (Holtshouse, 1998; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995, Mascitelli, 2000, p. 193). This suggestion flies in the face of the popular notion that information technology can eliminate barriers to knowledge exchange across oceans and time zones. If we accept the concept that tacit knowledge is fundamentally based on bodily experiences and emotional involvement, however, it is hard to imagine that something so personal can be digitised and downloaded. This is not to say that groupware and intranets are not essential tools for innovation; their effectiveness in the sharing of explicit knowledge is undeniable. So we are suggesting that simple steps can achieve important results in this regard. The frequent use of brief “stand-up meetings” for example, can help ensure continuous interaction among team members and encourage socialization and collaboration in innovative activities.

The authors of the book Enabling Knowledge Creation (Von Krogh et al., 2000) go even further in their discussion about effective knowledge creation within an organization. They argue that groups of people working together are more than just teams; they are microcommunities of knowledge. This is an important distinction, because “larger communities of knowledge can share certain practices, routines and languages, but for new tacit knowledge to emerge through socialization, the group must be small”. These teams are in a better position not only to create competitive position-enhancing knowledge, but also to communicate and integrate this knowledge back into their own areas and across the organization. One major challenge is that these microcommunities are typically not stable or perpetual. Unfortunately, through the dissolution of such microcommunities, most tacit knowledge gained and developed by them is lost. This knowledge can be retained only through the interactions that exist within the microcommunity itself, not through documents or manuals (Allred, 2001, p. 162).

Finally, the implementation of new knowledge and best practices must be measured and rewarded, supported by the culture and recognized by promotion decisions. Without attention to the implementation of knowledge, people are likely to learn information, but then fail to change their behaviour in beneficial ways.

Unlearning tacit knowledge

The opposite problem of sharing tacit knowledge lies in the unlearning of it. It has been suggested that the proponents of experiential knowledge may be the worst at unlearning, as the accumulation of such experiential knowledge required considerable investment of time and resources. Knowles and Saxberg (1988) also suggest that those who have invested heavily in their current knowledge may not be willing to unlearn. It would stand to reason that long-held views and knowledge acquired and reinforced over a long period of time may be considered more difficult to unlearn than recently acquired knowledge, to which the individual has less of an emotional attachment. This stands in contrary viewpoint when discussing absorptive capacity, claiming that without an appropriate knowledge base, new knowledge cannot be absorbed. Nonetheless, regardless of whether previously acquired knowledge helps unlearning or hinders it, previously acquired knowledge is recognised as having some influence on unlearning. Tacit knowledge, in particular, raises issues in relation to unlearning due to the fact that it is less easily identified or articulated, meaning it may be less easily challenged as part of the unlearning process (Becker, 2006).

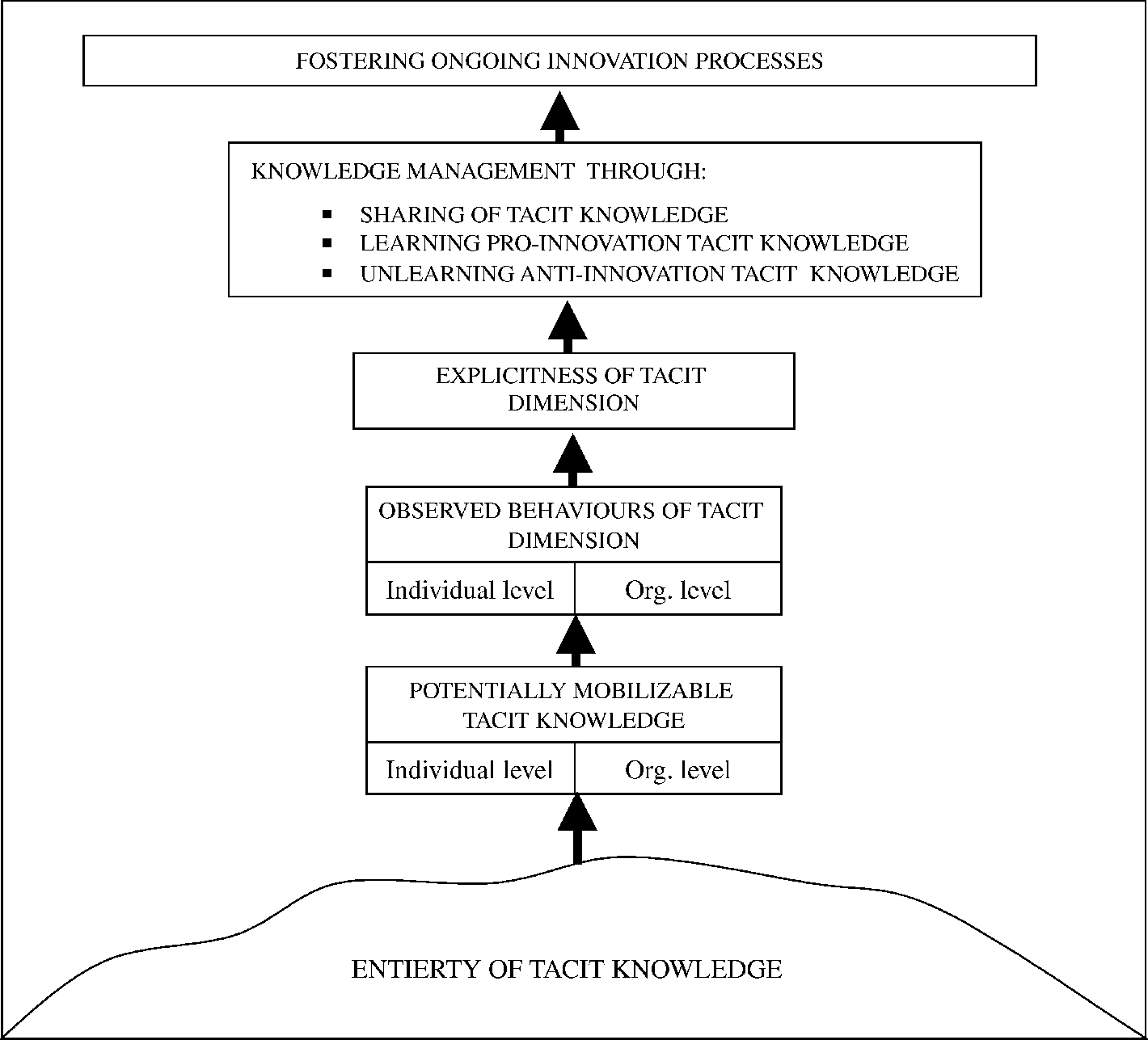

The main problem in studying tacit knowledge lies in the fact that it escapes observation and measurement. To study non-expressed knowledge an adequate methodology has to be developed. To summarize our understanding on managing tacit knowledge we propose a theoretical framework on how the process should be followed through:

- recognition of the tacit dimension on an individual level, as well as on an organizational level;

- observation of the behaviour deriving from individuals as well as organizational teams on the basis of possessed tacit knowledge;

- trying to make the behaviour explicit through sharing it;

- then learning of the new knowledge and simultaneous unlearning of obsolete and inadequate knowledge takes place; and

- such a process will further the actions needed for ongoing innovation to occur.

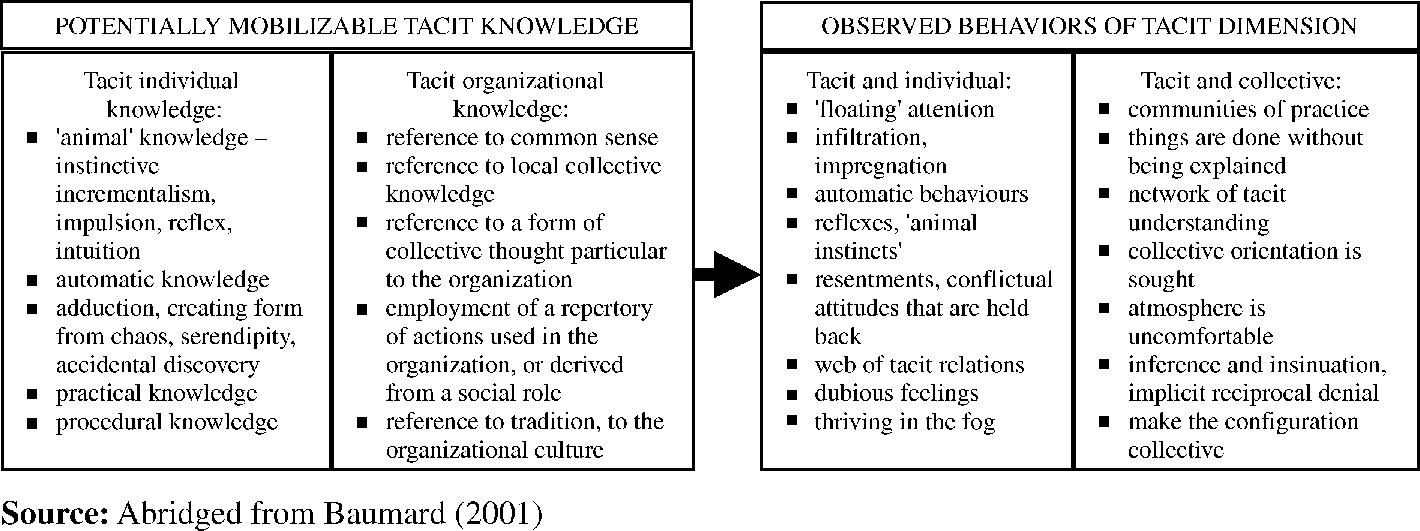

We are going to proceed by first presenting the two steps Baumard (2001) suggested in following tacit knowledge that can potentially be mobilized on an individual and organizational level, as well as observed behaviour deriving from it (Figure 3).

Although tacit knowledge constitutes a major part of what we know, it is difficult for organizations to fully benefit from this valuable asset. This is so because tacit knowledge is inherently elusive, and in order to capture, store and disseminate it, it is argued that it first has to be made explicit. However, such a process is difficult, and often fails due to three reasons (Stenmark, 2001, p. 9):

- we are not necessarily aware of our tacit knowledge;

- on a personal level, we do not need to make it explicit in order to use it; and

- we may not want to give up a valuable competitive advantage.

In Figure 4 we present a theoretical framework which could help us to overcome this perpetual elusiveness of tacit knowledge. Our understanding of the phenomena derives from the fact that tacit knowledge in its entirety is very difficult to recognize, and to benefit from. Our prepossession is, therefore, to bring forward tacit knowledge that can potentially be mobilized and observable through different manifestations of behaviour in order to make it explicit. Because only its explicitness would allow us to share it, as well as learn what needs to be learned, and unlearn those things that are outdated and obsolete. At this point it also has to be stressed that not all dimensions of tacit knowledge foster innovation processes. So an important knowledge management task would be to separate the tacit knowledge dimension, which is pro and contra the innovation processes. Having done this, it should no longer be difficult to put outstanding management efforts into the learning processes of those who are pro the learning processes and those who are contra the unlearning processes for innovation to occur.

Conclusion

Many have argued that we are in a knowledge economy in which intellectual capital is more important than land, labour and capital. Patents and many visible types of expertise alone will not, however, bring sustained competitive advantage. The exchange of knowledge among different agents is crucially important to the process in learning and creating absorptive capacity. The absorptive capacity of an organisation to embrace and implement knowledge in its environment can foster or impede the transfer of knowledge. Much of our knowledge is only the basis for a transient competitive advantage as our competitors reverse-engineer our products, copy our best practices and develop parallel (or superior) technologies. In contrast, tacit knowledge and superb knowledge management capabilities can form the basis of a relatively inimitable competitive advantage. Tacit knowledge can be spread within a firm but will be very difficult for other firms to copy. Superior knowledge-management capabilities are the basis for the rapid acquisition and spread of new knowledge and, therefore, foster continuous innovation and improvement.

We made some suggestions on how to manage tacit knowledge which will stimulate the innovation process so a company can gain and retain sustainable competitive advantage. To embrace incoming knowledge and use it productively a critical mass of knowledge and skills must already be present in the organization. Without an appropriate knowledge base, new knowledge cannot be absorbed. In the absorption process learning and unlearning take place. Learning and unlearning takes place continually in all knowledge areas and with all types of knowledge, which makes the phenomena very complex and hard to comprehend, especially because processes are mutually dependent on the social, cultural, economic and political contexts which are different from country to country.

To unleash the power of tacit knowledge in an organization the sharing and learning of tacit knowledge as well as its unlearning must be managed differently from explicit knowledge. Even though tacit knowledge is very elusive, it is possible to create a theoretical framework that could help bring forward tacit knowledge dimensions that are potentially capable of mobilization, and which are observable through different manifestations of behaviour. It is partly possible to make some dimensions of tacit knowledge explicit that not only contribute to successful sharing and mutual learning, but also enable the identification of those parts of knowledge that hinder innovation and should be unlearned. The better we understand the process of creating and using new knowledge and discarding obsolete knowledge, the more likely innovative behaviour will be fostered in organizations.

Figure 1A typology of attributes needed to

create new knowledge

Figure 2Simplified conceptual model for the

contribution of tacit knowledge to innovation

Figure 3Mobilizing tacit knowledge

Figure 4Framework for making tacit knowledge

visible

References

Allred, B. (2001), "Enabling knowledge creation: how to unlock the mystery of tacit knowledge and release the power of innovation", The Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 15 No.1, pp.161-2.

Argyris, C. (2004), On Organizational Learning, 2nd ed., Blackwell, Malden, MA, .

Argyris, C., Schon, D.A. (1978), Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, .

Armbrecht, F.M.R. Jr, Chapas, R.B., Chappelow, C.C., Farris, G.F. (2001), "Knowledge management in research and development", Research Technology Management, Vol. 44 No.4, pp.28-48.

Autio, E. (2005), Global Entrepreneurship Report, 2005 Report on High-Expectation Entrepreneurship, GEM, London Business School, London, .

Barrett, F.J., Thoman, G.F., Hocevar, S.P. (1995), "The central role of discourse in large-scale change: a social construction perspective", Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 31 No.3, pp.352-73.

Baumard, P. (2001), Tacit Knowledge in Organizations, Sage, London, .

Baumol, W. (1990), "Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive and destructive", Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98 pp.893-921.

Becker, K. (2006), "Individual and organisational unlearning: directions for future research", International Journal of Organisational Behaviour, Vol. 10 No.4, pp.659-70.

Christensen, P.R., Andersen, P.H., Damgaard, T., Munksgaard, K.B. (2004), "Internationalization of sourcing and knowledge development: an organizational routine perspective", paper presented at LOK Research Conference, Middelfart, 1-2 December 2003, .

Cummings, J. (2003), Knowledge Sharing: A Review of the Literature, The World Bank, Washington, DC, .

D'Aveni, R.A. (1994), Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering, The Free Press, New York, NY, .

Davenport, T.H. (1993), Process Innovation: Reengineering Work through Information Technology, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, .

Durrance, B. (1998), "Some explicit thoughts on tacit learning", Training & Development, Vol. 52 No.12, pp.24-9.

(2005), in Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M.A. (Eds),The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, Blackwell, Malden, MA, 1st paperback, .

Haldin-Herrgard, T. (2000), "Difficulties in diffusion of tacit knowledge in organizations", Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1 No.4, pp.357-65.

Hammer, M., Champy, J. (1993), Reengineering the Corporation, Harper Collins, New York, NY, .

Hedberg, B. (1984), "How organizations learn and unlearn", in Nystrom, P., Starbuck, W. (Eds),Handbook of Organizational Design, Cambridge University Press, London, .

Holan de, P., Phillips, N., Lawrence, T. (2004), "Managing organizational forgetting", MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 45 pp.45-51.

Holtshouse, D. (1998), "Knowledge research issues", California Management Review, Vol. 40 No.3, pp.277-80.

Huber, G.P. (1991), "Organizational learning: the contributing processes and the literatures", Organization Science, February, pp.88-115.

Johannessen, J.A., Olsen, B., Olaisen, J. (1999), "Aspects of innovation theory based on knowledge-management", International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 19 pp.121-39.

Johanson, J., Vahlne, J.E. (1990), "The mechanism of Internationalisation", International Marketing Review, Vol. 7 pp.11-24.

Kim, D.H. (1993), "The link between individual and organizational learning", Sloan Management Review, Vol. 35 No.1, pp.37-50.

Knowles, H.P., Saxberg, B.O. (1988), "Organizational leadership of planned and unplanned change: a systems approach to organizational viability", Futures, Vol. 20 pp.252-65.

Levitt, B., March, J.G. (1988), "Organizational learning", Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 14 pp.319-40.

Lubit, R. (2001), "The keys to sustainable competitive advantage: tacit knowledge and knowledge management", Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 29 No.3, pp.164-78.

Lynn, G.S. (1996), "Marketing and discontinuous innovation: the probe and learn process", California Management Review, Vol. 38 pp.8-37.

Mascitelli, R. (2000), "From experience: harnessing tacit knowledge to achieve breakthrough innovation", Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 17 No.3, pp.179-93.

Meso, P., Smith, R. (2000), "A resource-based view of organizational knowledge management system", Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 4 No.3, pp.224-34.

Minniti, M. (2006), Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2005 Executive Report, London Business School, London, .

Mulej, M. (2000), Dialektična in druge mehkosistemske teorije (podlaga za celovitost in uspeh managementa), EPF, Maribor, .

Nelson, R., Winter, G. (1982), An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, .

Newell, S., Robertson, M., Scarbrough, H., Swan, J. (2002), Managing Knowledge Work, Palgrave, New York, NY, .

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, .

Paoli, M., Principe, A. (2003), "Memory of the organization and memories within the organization", Journal of Management & Governance, Vol. 7 No.2, pp.145.

Polanyi, M. (1958), Personal Knowledge, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, .

Polanyi, M. (1966), The Tacit Dimension, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, .

Rebernik, M. (1997), "Beyond markets, hierarchies and ownership mania in transitional countries", Systems Research and Behavioural Science, Vol. 14 No.3, pp.83-194.

Rebernik, M. (1999), "Resources, opportunities and cooperation", in Lasker, G.E. (Eds),Advances in Support Systems Research, Decision Support Methodology for Human Systems Management and its Applications in Economics and Commerce, The International Institute for Advanced Studies in Systems Research and Cybernetics, Windsor, Vol. Vol. 5.

Rebernik, M., Mulej, M. (2000), "Requisite holism, isolating mechanisms and entrepreneurship", Kybernetes, Vol. 29 No.9/10, pp.1126-40.

Rebernik, M., Tominc, P., Pušnik, K. (2006), Podjetništvo med željami in stvarnostjo: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Slovenija 2005, Ekonomsko-poslovna fakulteta, Inštitut za podjetništvo in management malih podjetij, Univerza v Mariboru, Maribor, .

Roy, P., Roy, P. (2002), "Tacit knowledge management in organizations: a move towards strategic internal communications systems", Journal of American Academy of Business, Vol. 2 No.1, pp.28-32.

Schumpeter, J. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, .

Simon, H. (1991), "Bounded rationality and organizational learning", Organization Science, Vol. 2 No.1, pp.125-34.

Stein, E. (1995), "Organizational memory: review of concepts and recommendations for management", International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 15 No.2, pp.17-32.

Stenmark, D. (2001), "Leveraging tacit organizational knowledge", Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 17 No.3, pp.9-24.

Stewart, T.A. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations, DoubleDay, London, .

Svelby, K.E. (1997), The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-based Assets, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA, .

Tominc, P., Rebernik, M. (2006), "Growth aspirations and cultural support for entrepreneurship: a comparison of three post-socialist countries", Small Business Economics, Vol. 28 No.2/3, pp.239-55.

Von Krogh, E., Ichijo, K., Nonaka, I. (2000), Enabling Knowledge Creation: How to Unlock the Mystery of Tacit Knowledge and Release the Power of Innovation, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, .

Corresponding author

Miroslav Rebernik can be contacted at: rebernik@uni-mb.si